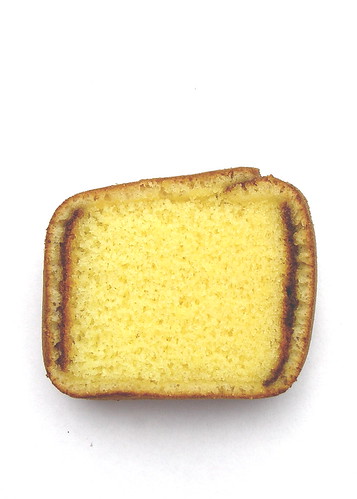

Day sixty-nine: Casutera Bunmeido, from ¥105 per slice

In 1543 a Portuguese ship wrecked on Tanegashima, a small island off the coast of Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan's main islands. The surviving sailors introduced the Japanese to an array of wonders, including soap, firearms, and a dense, eggy cake. At that time such cake was known in Portugal as pan de lo and in Spain as bizocho, but when the Japanese were told it came from the region of Castille, they dubbed the delicious import casutera.

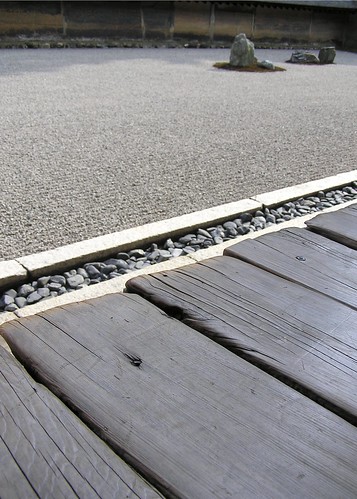

Like conpeito and a number of other sweet European treats, casutera found great favor among the Japanese and helped to open doors for Europeans who wished to trade or preach. By the 1630s Japanese authorities had a plan to limit foreign influence without cutting of the supply of desirable goods. In 1636, they built a fan-shaped artificial island in Nagasaki harbor on which to corral the their designated trading partners, the Dutch. Dejima had a single sea gate and one heavily guarded bridge connecting it to shore. (The land around Dejima was "reclaimed" from the harbor in 1904, and asphalt now laps the island's shores; one corner of its famous fan-shaped perimeter is clipped by a major roadway, making it very hard to understand how current plans to "restore" the island to its pre-1906 state could possibly succeed.)

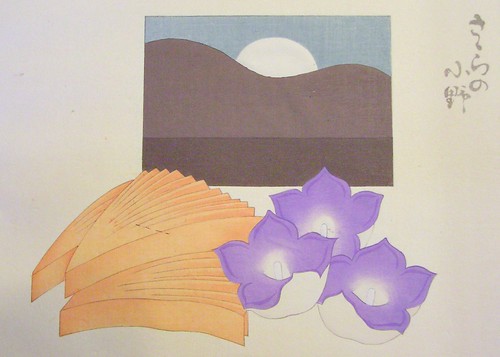

The port of Nagasaki originally opened to foreign trade in 1571, giving its citizens their first taste of imported sugar. When Dejima was built in 1636, sugar accounted for 2.2% of the total Dutch import; it was 15.7% by 1707, and the single greatest import item for most of the Edo period. At least three of the warehouses lining Dejima's single street were used to house sugar; the warehouse pictured below (right) was purpose-built for sugar storage. This sugar was certainly shipped all over Japan, but a great deal of it was consumed in Nagasaki--the local cuisine still has a reputation for being syrupy--and that's where casutera comes back in.

I came to Nagasaki to see Fukusaya (below, left and center), a casutera shop founded 1624 by a Portuguese-taught baker; its current proprietor is the 15th generation. Casutera never contains butter or oil, but depends for its moistness on a large proportion of well-whipped egg whites. Fukusaya's bakers separate the eggs, then whip the whites by hand in large copper bowls resting on rope-wrapped stands. Then then beat in the yolks, followed by brown sugar, white sugar, rice syrup, and flour; the recipe is adjusted slightly according to air temperature and humidity. The cake is baked in an automatic oven (rather than the old-fashioned charcoal-fired hikigama over--according to the company brochure, the only significant break with tradition) and allowed to rest for 24 hours, a period poetically known as "the return to sweetness". Fukusaya's casutera is famed for a particular side-effect of this hand-driven production process; crystals of brown sugar sink to the bottom of the pan and melt into a thin, gritty crust that connoisseurs adore biting into. Unfortunately, Fukusaya neither offers samples nor sells its casutera in anything smaller that a Costco-sized brick. So I bought my slice instead from Bunmeido, a lower-tier bakery. The cake was light, spongy, sweet--completely unobjectionable but not especially satisfying.

.jpg)