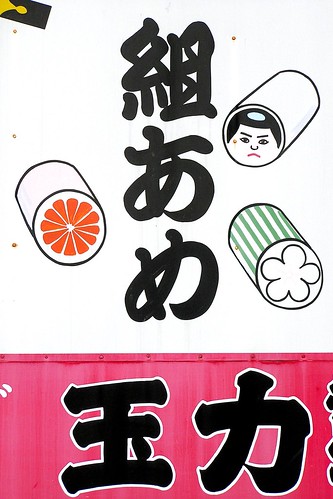

Day eighty-five: Kintaro Ame

Kintaro Ame Honten

Kintaro ame is a type of dagashi (cheap sweet) made in much the same way as those millefiori glass discs that feature so heavily in collectible paperweights. Hot malt syrup is kneaded by hand or machine until it turns into smooth stretchy ropes. The candy is quickly divided into batches to be dyed the different colors called for by the design. The colored bars are then stacked together carefully to create what looks like a hunk of cartoon log. The log is rolled and stretched, becoming thinner, cooler and more brittle.

Because kintaro ame can be made without heavy machinery (but with extra elbow grease), it is sometimes made in public at festivals or other events, where a crowd inevitably gathers in anticipation of the final step: with a dramatic flourish, the candymaker cracks the long thin rod crosswise, revealing the first sight of a recognizable--if distorted--face. As the name indicates, the face to appear most often over the years was that of Kintaro, a fabled boy hero of old stories, but today's kintaro ame are just as likely to depict contemporary characters such as Hello Kitty or Pokemon.

One of the last surviving manufacturers of kintaro ame, Tokyo's Kintaro Ame Honten, has taken modernization one step further: for the last decade, the company has produced batches of candy logos and portraits to order. Custom portraits of newlyweds are a particularly popular twist on the old tradition of giving bags of kintaro ame to wedding guests in order to secure a long and sweet future for the union. Even though the Japanese aphorism "Kintaro-ame no yo da" ("Just like Kintaro ame!") sneers at conformity, it seems that plenty of people want to adopt kintaro ame's charm and auspicious sweetness for their own.